For Jan

Originally published on April 6, 2014 in The Michigan Daily

Modeled off of the essay “Interstellar” by Rebecca McClanahan.

To be the daughter of a beautiful, older woman is to sit down in the memory of your childhood attic, your fingers running question marks around the edges of an old photograph. The lady in the picture stretches her arms into third position, neck arched with a grace you’ve never experienced (you with your stout soccer thighs and penchant for the hunch).

Not that you’ve ever tried to stand any differently. When she signs you up for ballet class you beg to be relieved of the aching pain of toe touches and pas de bourrées. You hate her for forcing you to leave the quiet wonder of the backyard, where you have been painstakingly constructing homes for ice fairies out of icicles and thumbprints in the snow.

You’ll call her fat and ugly when you fight, tell her that you don’t love her, but let her fold you into her arms when you cry. Her softness, the very thing that makes you embarrassed when she picks you up from school, is what comforts you, what lulls your shaking body into a slumber, head like a warm stone against the skin-smooth cradle of her breasts.

Your mom struggles to draw an audience to her shows. This isn’t a town for modern dance. You are dragged to all her rehearsals like a suitcase full of books, never paying much attention to the worry and the pride in her face when she sees her work fall into the bodies of the young — recent college graduates and talented immigrants from Taiwan, the Philippines and Cuba. You never imagine that she once was the one on the stage; spinning, rising and collapsing like a dandelion floret released on a breath of Chicago wind.

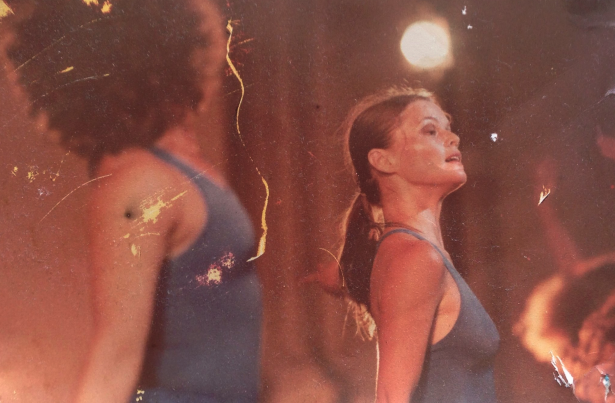

The pictures in the attic hint at that story, though it will take you a decade to believe it. In them she’s as young and beautiful as a babysitter, a news anchor, an old-timey movie star. Sometimes she wears strange and wonderful costumes: long nails and a flowered headdress or a blue veil and jeweled leotard. You find one picture of her smoking on a train, lips half-parted and eyes unsmiling, fixed on a phantom photographer (another man? It couldn’t be your father).

She never smokes now, just half a Corona or ice-spiked glass of wine with dinner. When did she become so boring? you wonder. You never pause to consider that you might have been the reason, that it was you who tore the hole in your mother’s beauty and let the small dignities escape, the wrinkles spread, the air deflate. You tell her you think her dancing is weird. You don’t bring many friends to her shows, don’t hand out the flyers she gives you at school. They settle at the bottom of trashcans heavier than the guilt you brush off when she asks you about them later. Yeah, a couple people said they might go.

Her talent survives your betrayal. More than 15 years later, you watch her smile and wave to the audience from under the blinding lights of the stage, thanking you and your father for always being there, always supporting her. She has taken her company across the country and beyond its borders: Mexico, Cuba and maybe Germany in the next couple years. Her body of work is larger and older than you, her achievements greater and begotten with more sacrifice than you can ever imagine, more than you yourself may ever accomplish. At the age of 62 she still radiates an almost elvish beauty — eyes the blue of Superior and cheekbones high and cut from the ore of Iron River. She is bottle blonde, but it could be natural, she could be much younger, how did you not see it until now?

The woman in the pictures still dances in time with an unheard music, still one-two-three’s and plucks the hearts out of the chests of anyone who dares to watch. You want to drag the whole world to her shows, want to sit the President down and pop in a VHS tape of her spinning, spinning, spinning — all the while holding you, protecting you from yourself.